This has been an exciting few weeks in author land. I saw some first mockups for my US covers and gave feedback. I saw a a finished version of my German cover. I saw mockups for the inside pages of my US edition. I’m incredibly excited about the covers, which are both gorgeous. And most importantly, they have my name on them. Right there on the cover! It says Linnea Hartsuyker! Or actually LINNEA HARTSUYKER since both editions are using an all-caps font. SO MANY PEOPLE WILL BE MISPRONOUNCING MY NAME SOON!

This has been an exciting few weeks in author land. I saw some first mockups for my US covers and gave feedback. I saw a a finished version of my German cover. I saw mockups for the inside pages of my US edition. I’m incredibly excited about the covers, which are both gorgeous. And most importantly, they have my name on them. Right there on the cover! It says Linnea Hartsuyker! Or actually LINNEA HARTSUYKER since both editions are using an all-caps font. SO MANY PEOPLE WILL BE MISPRONOUNCING MY NAME SOON!

I also got my first blurb from a reader, which was incredibly complimentary, and good to read, because this week I also tackled my current draft of The Sea Queen.

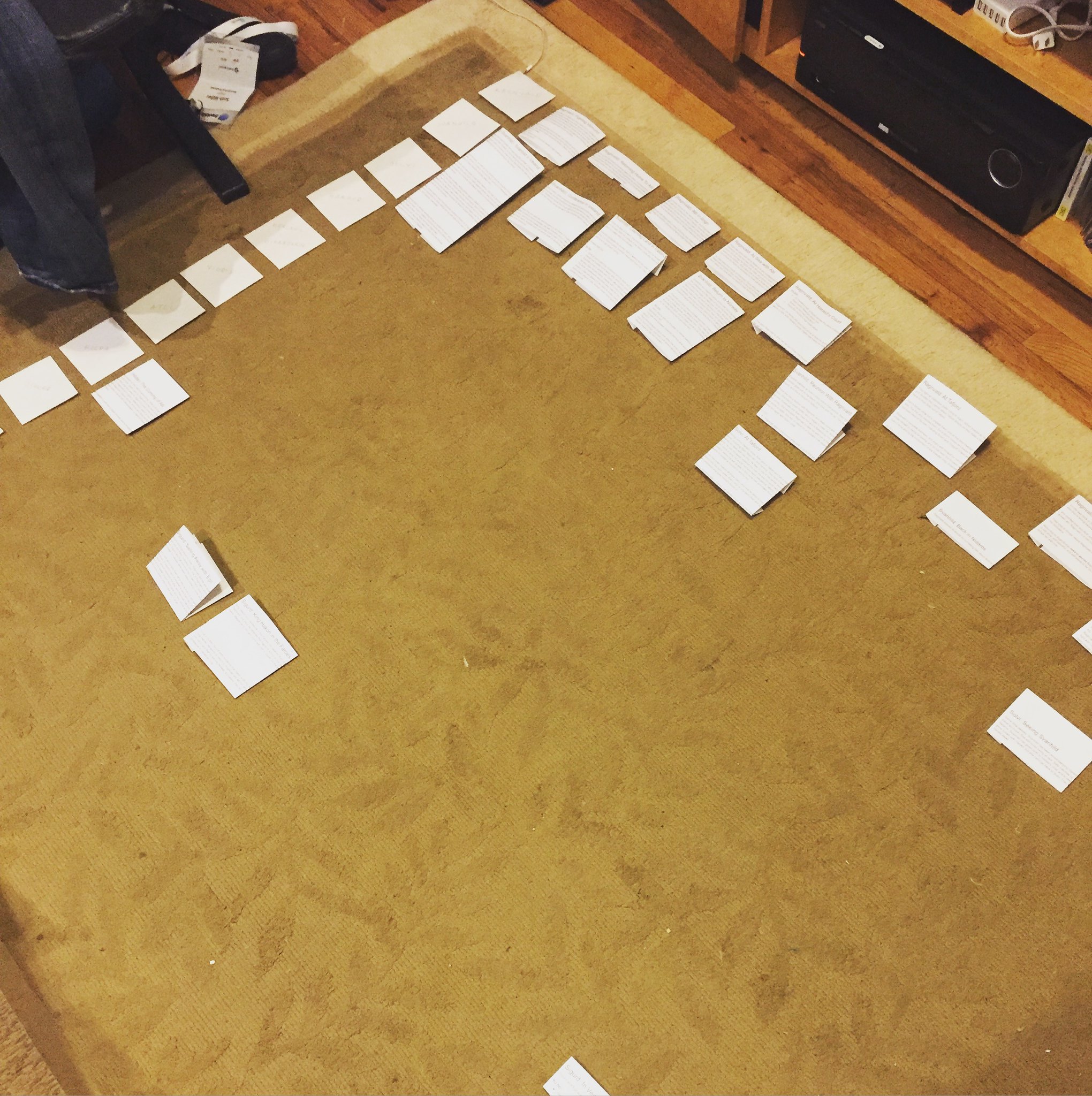

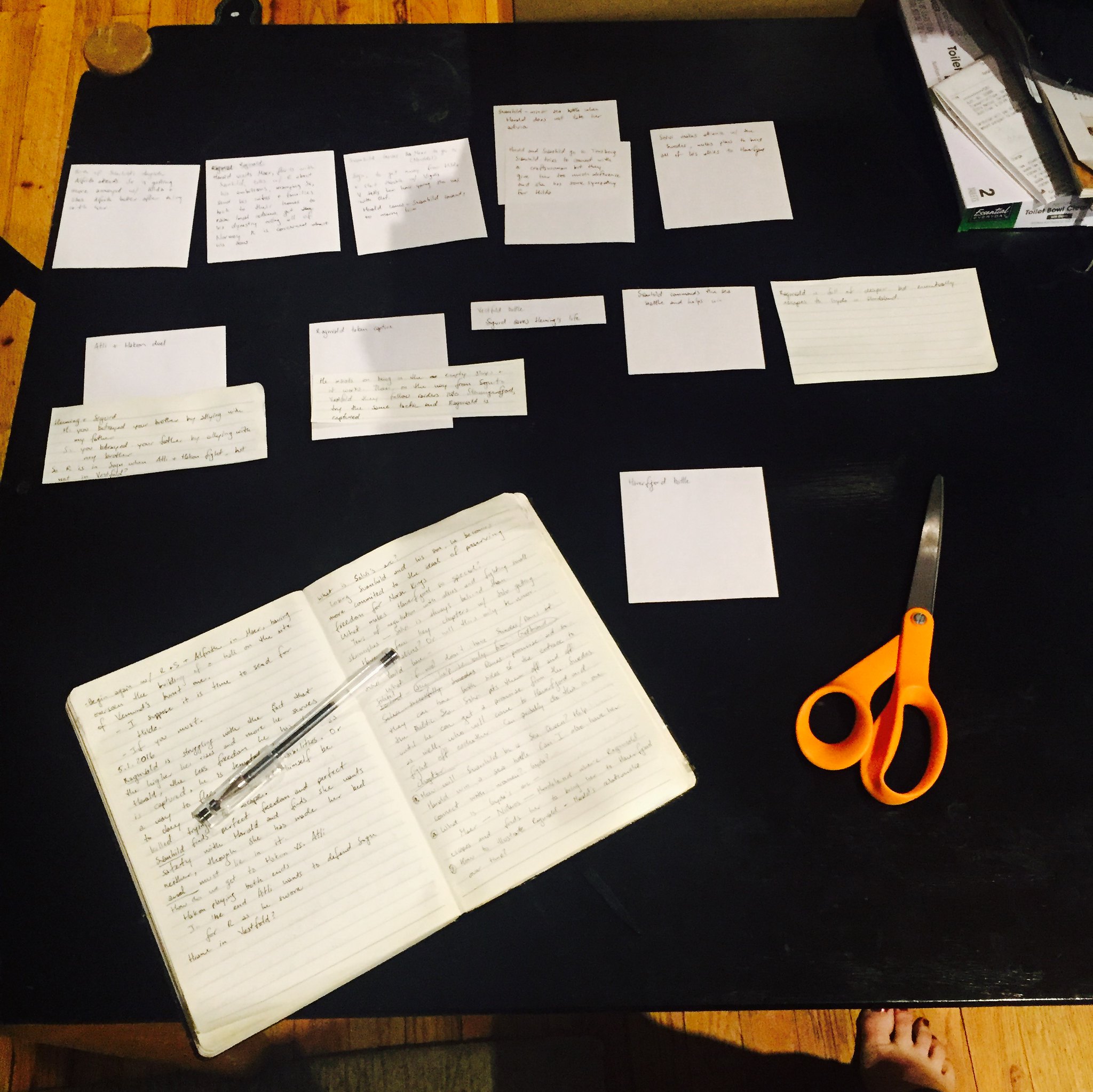

In late January 2016, I started writing The Sea Queen. On May 31, 2016, I was about 70% through writing a rough draft that followed my plot outline, but the thing with writing a rough draft, for me anyway, is that I’m always adding plot points. Oh, I should have a feud. That feud is based on this event. That I forgot to put in the first time around, but now I will leave a note that says ‘insert event that incites feud here’. And I can go on, working forward, making notes to myself for a while. But as I neared the end, I realized I had a pile of vaguely defined plot threads, some missing beginnings, some missing endings. I knew I needed almost all of my characters to come together at the ending, but I didn’t know where some of them were coming from, so I didn’t know how to get them there.

I spent all summer working on what I’m calling the first draft, which is a complete, somewhat coherent novel, 178,000 words, which I finished writing 2 weeks ago. I took 10 days off from it (longest 10 days of my life), and then over the last 4 days, I read it on my Kindle, making overall notes and notes on each chapter about what needs fixing. The short answer: EVERYTHING.

The longer answer is 4500 words of notes, dividing into chapter-related notes and notes overall.

- Overall, the whole thing is very rushed, which is concerning because it is also quite long already. Almost every scene needs more set up, more time to live, and a better off ramp. Almost every scene needs more description. Almost every scene needs more explanation and more inner life for the characters. (Not the first sea battle though. I wrote an awesome sea battle.) Some scenes are hardly better than notes.

- I indulged in any number of annoying writing tics, and must have thought they were cute at the time. They are not.

- Every character’s arc needs to be amplified and clarified. Motivations and emotions are muddled right now. They need to be clear and sharp, except when ambivalence is the point.

- A few characters need more to do.

- I’ve neglected or flattened some points of conflict that I can make much more dramatic

- A few plot threads don’t connect

The good news is that overall the plot is very solid. Many disparate threads come together for an ending that is both surprising and inevitable. I was pleased about that when I finished writing the first draft, and am still pleased about that now.

And I shouldn’t be so surprised that on a more micro level, this draft has so many problems. I chose not to massage scenes or sentences, since the purpose of this draft was to get the plot right. I wanted to be able to step back and look at the book as a whole before doing detailed work on sentences that might not survive into another draft.

I think for the next book, though, I will do the 70% thing again, but when I move from the rough draft to the first draft, I will pay more attention to scenes, paragraphs, and sentences, because this book was quite a chore to read, except for a few shining chapters.

Today I am going to start revisions which will mean going to go through each chapter again and actually making the changes I have in mind. I will edit each chapter a couple times on this pass, asking myself the following questions about each scene:

- Who is in the scene? Make sure the reader knows this.

- Where is the scene? Make sure the reader can see/hear/smell/taste/touch it.

- What are the emotions in the scene? Make sure the reader can feel them.

- How do the characters react in the scene? For the love of all that is holy, stop ending your scenes with a piece of dialog and no reaction from anyone. Maybe once or twice it’s okay, but for sure not every time.

I’ve also created a list of danger words that are signposts for when I’m about to mangle a sentence, and another list of words I use too frequently. I will be examining each chapter for these words and making sure that if I use them, I’m doing so with purpose and clarity.

It’s a lot to do, but I can’t wait to get started.

When I applied to MFA programs, I used the first few chapters of The Half-Drowned King as my portfolio material, which usually counts for 80-90% of the admissions decision. I wanted MFA faculty to know that I was a writer of historical fiction, with swords and kings, and prophetic dream right in chapter one. I was worried that MFA programs would be full of literary snobs, and I wanted the program that chose me to know what they were getting.

When I applied to MFA programs, I used the first few chapters of The Half-Drowned King as my portfolio material, which usually counts for 80-90% of the admissions decision. I wanted MFA faculty to know that I was a writer of historical fiction, with swords and kings, and prophetic dream right in chapter one. I was worried that MFA programs would be full of literary snobs, and I wanted the program that chose me to know what they were getting.

Mike Carey’s

Mike Carey’s