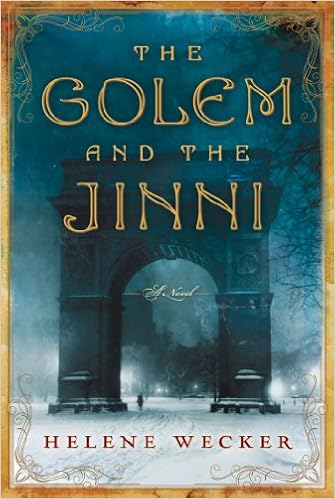

I read The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker a while ago, and recently decided to re-read it. It is the story of a newly created female golem who immediately loses her master, and a jinni trapped in human form, both of whom end up in fin de siècle New York and have to create new lives for themselves. It is a book that is easy to get lost in, and makes me excited about the mixing of literary and genre fiction. They’re excellent separate, of course, a good literary dissection of a marriage, or a life, where the drama comes from everyday triumphs and tragedies. And I love a good pulpy fantasy novel, with serviceable prose, and well-worn tropes make the reading feel like putting on comfy old sweatshirt.

I read The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker a while ago, and recently decided to re-read it. It is the story of a newly created female golem who immediately loses her master, and a jinni trapped in human form, both of whom end up in fin de siècle New York and have to create new lives for themselves. It is a book that is easy to get lost in, and makes me excited about the mixing of literary and genre fiction. They’re excellent separate, of course, a good literary dissection of a marriage, or a life, where the drama comes from everyday triumphs and tragedies. And I love a good pulpy fantasy novel, with serviceable prose, and well-worn tropes make the reading feel like putting on comfy old sweatshirt.

But I am thrilled about novels like this, a literary novel with an urban fantasy plot. Like the best literary novels, it creates complicated, not always likable characters, and wrings as much drama from the little ways that they choose to get through their days as the more operatic confrontations of the ending.

I also admire the way the author narrates the novel in an omniscient voice. I am more familiar with omniscient voice in 19th century novels, where the narrator has a particular point of view and that voice is as much a part of the novel as any of the characters. Who is it that tells us that “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife” if not the author? (I will leave aside whether that author is Jane Austen or the persona that she is putting on for another day.) It is Thackeray’s voice for Vanity Fair that endears Becky Sharp to us, because his affection for her is so evident, even with all her cruelties and vanities.

The voice in The Golem and the Jinni is more subdued, but still very skillful. The point of view moves from character to character, smoothly, and when necessary, tells the reader about things outside the characters’ sphere of knowledge. It also goes deeply into individual characters so that we know them inside and out. It has all the advantages of a shifting third person, with just a bit more. It helps give the novel a slightly old fashioned feel, in keeping with its setting. Omniscient third has fallen somewhat out of favor these days.

What it accomplishes by going so deep into point of view and then coming out of it, is an intimacy that many modern books in omniscient third lack. The switches happen so seamlessly that it gives the narrator a remarkable freedom.

By creating two creatures who are new to turn-of-the-century New York City, she gets to give them the joy of exploring this place and time, and letting the reader explore with them. That is not something that I’ve gotten to do in the historical fiction I’ve written so far, where all of my characters are more or less familiar with their milieu, although each of them pushes their boundaries. This book is a good reminder to sit in those moments when my characters are in a new situation, a new place, give them time to discover it, be inspired by it or afraid of it, whatever their personality dictates.

I’ve never wanted to write reviews here, rather to talk about books that I’ve enjoyed, and what I’ve learned from them. It’s interesting to see some reviews on Goodreads saying that it has far too much description of old New York, when I could have read twice as much. I don’t think it’s a perfect book–I’m not sure such a thing exists–but it worked, and it was intelligent and thoughtful, charming and moving, and I highly recommend it.